Circuit Breaker

Why are they used?

A circuit breaker is used to provide stability and prevent cascading failures in distributed systems. These should be used in conjunction with judicious timeouts at the interfaces between remote systems to prevent the failure of a single component from bringing down all components.

As an example, we have a web application interacting with a remote third party web service.

Let’s say the third party has oversold their capacity and their database melts down under load.

Assume that the database fails in such a way that it takes a very long time to hand back an error to the third party web service. This in turn makes calls fail after a long period of time. Back to our web application, the users have noticed that their form submissions take much longer seeming to hang. Well the users do what they know to do which is use the refresh button, adding more requests to their already running requests. This eventually causes the failure of the web application due to resource exhaustion. This will affect all users, even those who are not using functionality dependent on this third party web service.

Introducing circuit breakers on the web service call would cause the requests to begin to fail-fast, letting the user know that something is wrong and that they need not refresh their request. This also confines the failure behavior to only those users that are using functionality dependent on the third party, other users are no longer affected as there is no resource exhaustion. Circuit breakers can also allow savvy developers to mark portions of the site that use the functionality unavailable, or perhaps show some cached content as appropriate while the breaker is open.

The Apache Pekko library provides an implementation of a circuit breaker called CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker which has the behavior described below.

What do they do?

-

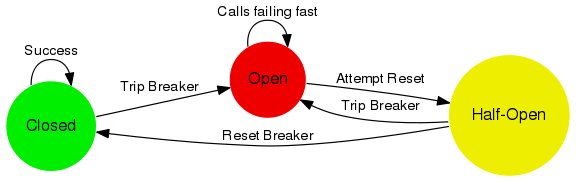

During normal operation, a circuit breaker is in the Closed state:

- Exceptions or calls exceeding the configured callTimeout increment a failure counter

- Successes reset the failure count to zero

- When the failure counter reaches a maxFailures count, the breaker is tripped into Open state

-

While in Open state:

- All calls fail-fast with a

CircuitBreakerOpenExceptionCircuitBreakerOpenException - After the configured resetTimeout, the circuit breaker enters a Half-Open state

- All calls fail-fast with a

-

In Half-Open state:

- The first call attempted is allowed through without failing fast

- All other calls fail-fast with an exception just as in Open state

- If the first call succeeds, the breaker is reset back to Closed state and the resetTimeout is reset

- If the first call fails, the breaker is tripped again into the Open state (as for exponential backoff circuit breaker, the resetTimeout is multiplied by the exponential backoff factor)

-

State transition listeners:

- Callbacks can be provided for every state entry via

onOpenonOpen,onCloseonClose, andonHalfOpenonHalfOpen - These are executed in the

ExecutionContextprovided.

- Callbacks can be provided for every state entry via

-

Calls result listeners:

- Callbacks can be used eg. to collect statistics about all invocations or to react on specific call results like success, failures or timeouts.

- Supported callbacks are:

onCallSuccessonCallSuccess,onCallFailureonCallFailure,onCallTimeoutonCallTimeout,onCallBreakerOpenonCallBreakerOpen. - These are executed in the

ExecutionContextprovided.

Examples

Initialization

Here’s how a CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker would be configured for:

- 5 maximum failures

- a call timeout of 10 seconds

- a reset timeout of 1 minute

- Scala

-

source

import scala.concurrent.duration._ import org.apache.pekko import pekko.pattern.CircuitBreaker import pekko.pattern.pipe import pekko.actor.{ Actor, ActorLogging, ActorRef } import scala.concurrent.Future import scala.util.{ Failure, Success, Try } class DangerousActor extends Actor with ActorLogging { import context.dispatcher val breaker = new CircuitBreaker(context.system.scheduler, maxFailures = 5, callTimeout = 10.seconds, resetTimeout = 1.minute) .onOpen(notifyMeOnOpen()) def notifyMeOnOpen(): Unit = log.warning("My CircuitBreaker is now open, and will not close for one minute") - Java

-

source

import org.apache.pekko.actor.AbstractActor; import org.apache.pekko.event.LoggingAdapter; import java.time.Duration; import org.apache.pekko.pattern.CircuitBreaker; import org.apache.pekko.event.Logging; import static org.apache.pekko.pattern.Patterns.pipe; import java.util.concurrent.CompletableFuture; public class DangerousJavaActor extends AbstractActor { private final CircuitBreaker breaker; private final LoggingAdapter log = Logging.getLogger(getContext().system(), this); public DangerousJavaActor() { this.breaker = new CircuitBreaker( getContext().getDispatcher(), getContext().getSystem().getScheduler(), 5, Duration.ofSeconds(10), Duration.ofMinutes(1)) .addOnOpenListener(this::notifyMeOnOpen); } public void notifyMeOnOpen() { log.warning("My CircuitBreaker is now open, and will not close for one minute"); }

Future & Synchronous based API

Once a circuit breaker actor has been initialized, interacting with that actor is done by either using the Future based API or the synchronous API. Both of these APIs are considered Call Protection because whether synchronously or asynchronously, the purpose of the circuit breaker is to protect your system from cascading failures while making a call to another service. In the future based API, we use the withCircuitBreakercallWithCircuitBreakerCS which takes an asynchronous method (some method wrapped in a FutureCompletionState), for instance a call to retrieve data from a database, and we pipe the result back to the sender. If for some reason the database in this example isn’t responding, or there is another issue, the circuit breaker will open and stop trying to hit the database again and again until the timeout is over.

The Synchronous API would also wrap your call with the circuit breaker logic, however, it uses the withSyncCircuitBreakercallWithSyncCircuitBreaker and receives a method that is not wrapped in a FutureCompletionState.

- Scala

-

source

def dangerousCall: String = "This really isn't that dangerous of a call after all" def receive = { case "is my middle name" => breaker.withCircuitBreaker(Future(dangerousCall)).pipeTo(sender()) case "block for me" => sender() ! breaker.withSyncCircuitBreaker(dangerousCall) } - Java

-

source

public String dangerousCall() { return "This really isn't that dangerous of a call after all"; } @Override public Receive createReceive() { return receiveBuilder() .match( String.class, "is my middle name"::equals, m -> pipe( breaker.callWithCircuitBreakerCS( () -> CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(this::dangerousCall)), getContext().getDispatcher()) .to(sender())) .match( String.class, "block for me"::equals, m -> { sender().tell(breaker.callWithSyncCircuitBreaker(this::dangerousCall), self()); }) .build(); }

Using the CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker’s companion object applyCircuitBreaker.create method will return a CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker where callbacks are executed in the caller’s thread. This can be useful if the asynchronous FutureCompletionState behavior is unnecessary, for example invoking a synchronous-only API.

Control failure count explicitly

By default, the circuit breaker treats Exception as failure in synchronized API, or failed FutureCompletionState as failure in future based API. On failure, the failure count will increment. If the failure count reaches the maxFailures, the circuit breaker will be opened. However, some applications may require certain exceptions to not increase the failure count. In other cases one may want to increase the failure count even if the call succeeded. Pekko circuit breaker provides a way to achieve such use cases: withCircuitBreaker and withSyncCircuitBreakercallWithCircuitBreaker, callWithSyncCircuitBreaker and callWithCircuitBreakerCS.

All methods above accept an argument defineFailureFn

Type of defineFailureFn: Try[T] => BooleanBiFunction[Optional[T], Optional[Throwable], Boolean]

This is a function which takes in a Try[T] and returns a Boolean. The Try[T] correspond to the Future[T] of the protected call. The response of a protected call is modelled using Optional[T] for a successful return value and Optional[Throwable] for exceptions. This function should return true if the call should increase failure count, else false.

- Scala

-

source

def luckyNumber(): Future[Int] = { val evenNumberAsFailure: Try[Int] => Boolean = { case Success(n) => n % 2 == 0 case Failure(_) => true } val breaker = new CircuitBreaker(context.system.scheduler, maxFailures = 5, callTimeout = 10.seconds, resetTimeout = 1.minute) // this call will return 8888 and increase failure count at the same time breaker.withCircuitBreaker(Future(8888), evenNumberAsFailure) } - Java

-

source

private final CircuitBreaker breaker; public EvenNoFailureJavaExample() { this.breaker = new CircuitBreaker( getContext().getDispatcher(), getContext().getSystem().getScheduler(), 5, Duration.ofSeconds(10), Duration.ofMinutes(1)); } public int luckyNumber() { BiFunction<Optional<Integer>, Optional<Throwable>, Boolean> evenNoAsFailure = (result, err) -> (result.isPresent() && result.get() % 2 == 0); // this will return 8888 and increase failure count at the same time return this.breaker.callWithSyncCircuitBreaker(() -> 8888, evenNoAsFailure); }

Low level API

The low-level API allows you to describe the behavior of the CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker in detail, including deciding what to return to the calling ActorActor in case of success or failure. This is especially useful when expecting the remote call to send a reply. CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker doesn’t support Tell Protection (protecting against calls that expect a reply) natively at the moment. Thus you need to use the low-level power-user APIs, succeedsucceed and failfail methods, as well as isClosedisClosed, isOpenisOpen, isHalfOpenisHalfOpen to implement it.

As can be seen in the examples below, a Tell Protection pattern could be implemented by using the succeedsucceed and failfail methods, which would count towards the CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker counts. In the example, a call is made to the remote service if the breaker.isClosedbreaker.isClosed. Once a response is received, the succeedsucceed method is invoked, which tells the CircuitBreakerCircuitBreaker to keep the breaker closed. On the other hand, if an error or timeout is received we trigger a failfail, and the breaker accrues this failure towards its count for opening the breaker.

The below example doesn’t make a remote call when the state is HalfOpen. Using the power-user APIs, it is your responsibility to judge when to make remote calls in HalfOpen.

- Scala

-

source

import org.apache.pekko.actor.ReceiveTimeout def receive = { case "call" if breaker.isClosed => { recipient ! "message" } case "response" => { breaker.succeed() } case err: Throwable => { breaker.fail() } case ReceiveTimeout => { breaker.fail() } } - Java

-

source

@Override public Receive createReceive() { return receiveBuilder() .match( String.class, payload -> "call".equals(payload) && breaker.isClosed(), payload -> target.tell("message", self())) .matchEquals("response", payload -> breaker.succeed()) .match(Throwable.class, t -> breaker.fail()) .match(ReceiveTimeout.class, t -> breaker.fail()) .build(); }